CONTENT

The story of two sheets of iron

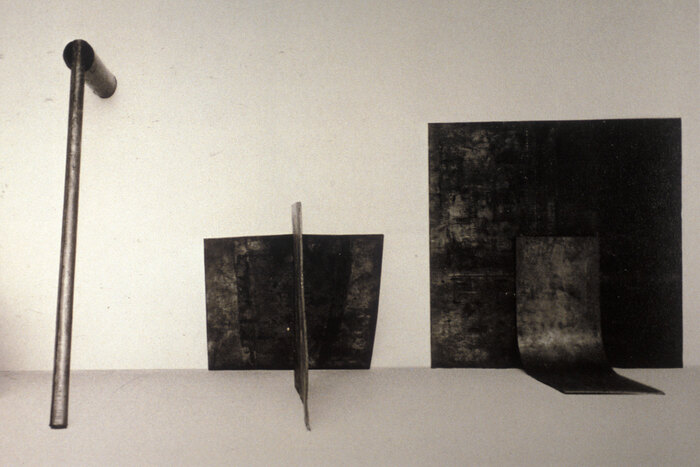

According to Richard Serra two sheets of iron are enough to form a piece of art. The longer one stands upright and is positioned with one end perpendicular against a wall, the other sheet, shorter but of the same height, leans against the first, fixing it in its upright position. The relation of both elements is straightforward – we could say self-explaining. The weight of the second is keeping the first one upright. The simplicity of this composition creates a multiplicity of different spaces and experiences. Put in place the once homogeneous space has been differentiated into uncountable species of spaces, each different from the other.

Each sheet, thanks to its opacity, stops our gaze on its surface promising another world behind it. Seen from one direction the cut surface is clearly visible and the sheet becomes a line. Seen from another direction the sheet becomes a surface. Around it there are other surfaces made of other materials. Together they form a mosaic of surfaces, which changes continuously while we are moving through space. The large iron sheet encounters the white walls of the building to its right and above it, the first directly the second only visually. Their different lightness emphasizes their relation. Below it meets the dark grey surface of the pavement, full of imperfections of different sizes and origins. The contrast between them is much less pronounced here. To the left there is the smaller iron sheet. Iron meets iron. The smaller sheet meets the larger one exactly in one point – only a fraction of a square millimetre large, but enough to unload all its weight, while keeping its upper angles afloat in space.

At this same point their contour lines meet and come into relation with all the other lines around them underlining their presence in space. On a different level the iron surfaces, marked through their transportation and covered with strains of flash rust, present a blurred image of their surroundings drawn by the light rays reflected or emanated around them. The closer we get to both elements the more spaces we encounter, the signals our eyes receive are complemented through the different temperature the iron emits, the change in acoustic our ears perceive, the different smell of the material our nose detects.

At this same point their contour lines meet and come into relation with all the other lines around them underlining their presence in space. On a different level the iron surfaces, marked through their transportation and covered with strains of flash rust, present a blurred image of their surroundings drawn by the light rays reflected or emanated around them. The closer we get to both elements the more spaces we encounter, the signals our eyes receive are complemented through the different temperature the iron emits, the change in acoustic our ears perceive, the different smell of the material our nose detects.

It is at a very fundamental level that materials shape our perception of the world, such as the experience we have while our body passes through an opening in a wall made out of stone while entering a cooler place defined by that wall. The experience we have while we open a door by touching a metal door handle, feeling its temperature or the experience we have while we walk on a wooden pavement continuously reminds us of our own body.

©

©

It is the most profound condition of architecture – to be corporeal – not only in its experience, but also in its existence. The fact that objects are defined by the matter they are made of, that two objects might share the same geometry, but be made out of different materials resulting in different qualities capable of producing different experiences, the fact that we can identify a thing because of its distinct shape, weight, texture, temperature, odour, sound and that those qualities distinguish it from other objects, is described in German with the two words Objekthaftigkeit and Materialhaftigkeit. Whereas Objekthaftigkeit defines the fundamental condition of being a recognizable object: the thingness of objects; Materialhaftigkeit refers to the relation an object has to its material, to matter: the materialness of things.

They have their own spirit

This is a testimony to the fact that matter alone has already all the necessary complexity to sustain a rich discourse of design practice. This is true for all the applied arts. There is no need to fall back on anything from outside the material realm, outside of practice. Art, architecture and design are practices, not sciences. Whereas the construction of sciences aspire to universal application, following Dave Hickey, pictures and buildings only need to work where they are. The concreteness of practice in opposition to the abstraction of theory: matter versus theory, material versus idea is ultimately the concrete versus the abstract.

The idea that materials already possess an infinite amount of ways of expressing themselves brings us to a point where we have to realize that they have their own spirit not ours. It is Richard Serra who noted that we are obliged to follow them, when we are on search for the singularity of a certain matter or better of a certain material instead of a form and that by doing so we are committed to the continuous variation of variables, instead of the extrapolation of constants. A quite detailed definition, because it clearly separates the non predefined outcome of an inventive process from everything that has nothing to do with it, such as the extrapolation of secure constants through methods, formulae, manuals, etc., which are innated to the abstract sciences.

Following this direction we could define the action of designing something as a form of Matterography, as an action which derives its knowledge directly from the investigation and description of material facts and their application in a process of creation, as opposed to the realm of Ideology, where the supposed superiority of logic interprets an idea by shifting it between different spatial realms, constantly in danger of not realizing the ontological changes deriving from the passage from one space to the other and more often than not putting faith in the instruments of logic.

Some piles of felt compressed by a heavy sheet of iron and the inherent opportunity to wrap them, to stack them, contain, amongst others, the possibility of a space with a peculiar warmth, with a unique acoustic which could be complemented by something like a piano. It is the material, which reminds us to follow the instruments of the concrete rather than the instruments of abstraction.

Deduce/produce

As a matter of fact the knowledge we derive from such an attitude is much more intense when discovered directly and not mediated through the abstract realm of theory. Matter does not follow an idea – it is the other way round. The question is whether we are able to observe matter and deduce its possible expressions, whether we are able to comprehend it by observation, whether we are patient enough to observe a phenomena, a physical phenomena, existing structures or actions. It is essential to be able to brush aside everything superfluous: preconceptions, common places, everything you might have heard or read but never felt, never experienced, never verified. This is an attitude where you let things go their course in order to help ideas raise from inside your head.

©

©

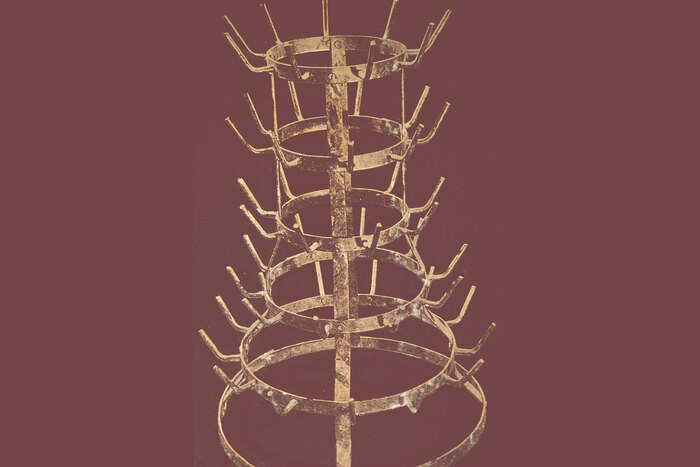

Almost readymade but only nearly. When Duchamp does his first readymade objects he very much proceeds the same way. He follows matter, the materials, the elements and objects he encounters. He collects, observes and assembles elements following them as closely as possible. It is just them and us, nothing more.

Architecture is an applied art. To design implies nothing less than the appearance of what has not been there before, which is always a process of invention and as Sir John Soane pointed out: Invention is the most painful activity of the human mind. But this does not mean it is abstract, it is quite the opposite – it is directly connected to the concreteness of careful observation and deduction, to the subversive energy of invention and surprise.

Applied arts are, as suggested by Levi Strauss, in the middle between abstract science and magical thought, and I would like to add that they are mediated through the constraints of the material realm. It is again Strauss who contrasts the world of the engineer with its infinite set of instruments and materials, with the world of the bricoleur, with its defined set of instruments and resources. With other words the world of the artist, architect and designer has to be seen as an economy of availability and ability, of the concreteness of all the resources we have, of everything we have nearby or might encounter.

It is quite simple: for an architect it is sufficient to encounter a pile of glass bricks or the availability of a huge amount of cheap Quonset houses to design a piece of architecture as Pierre Chareau did or to encounter a pile of tiles as Arturo Franco did. No method, no copies, no manual, no formula, just a question of being able to observe, deduce, invent or with the words of Arturo Franco a question of economy, ability and resources. It is about the ability to deduce a possible syntax from a material or an element, to invent a way how to connect two materials or elements, how to keep them together.

©

©

It is precisely because thingness and materiality are so fundamental for the applied arts that we can leave materials in their raw state and create very sophisticated designs with very basic materials. It is for the same reason that we can use errors and mistakes, which might arise during the design process, to our advantage.

But the concept of matter and of the material can be extended even one step further. Materials qualify spaces through the manipulation of their spatial qualities. It is precisely through their constraints that materials become expressive. This means also that as soon as we encounter a constraint we are confronted with a material condition. As a matter of fact this applies not only to physical constraints such as strength, density, weight but also to social, legislative and programmatic constraints which are related to some sort of material realm as well. And as soon as we encounter a material condition this condition with its constraints enables us to invent a corresponding compositional grammar, very much like the five points of Le Corbusier.

Stephan Jung

KEYWORDS

AVAILABLE

SAFT 02 MATTER

is also available as part of:

Buy it now !