CONTENT

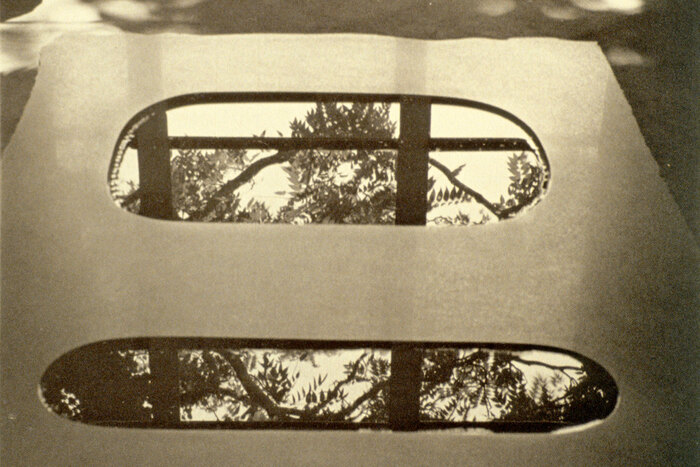

A volume of black granite is placed on the ground. It is about 130 cm long, circa 82 cm wide and some 37 cm high. A cut has taken away some of its mass in the lower part, producing a distinct L shaped section. The subtracted volume has been replaced by a pink granite boulder, which raises the now thinner end keeping the top even. As a result each side of the volume has a distinct composition. Whereas on one side the volume unloads its weight directly on the ground, on the opposing side an oval form suspends the weight of the black granite. A well-devised encounter of two different shapes, a small lesson of architectural composition, the mass of the granite in a state of disequilibrium, kept suspended in the air by a smaller piece of a different material.

The flanks of black granite have been left raw, exposing the way the block has been broken, the side which is left at full height is particularly rough, but the top has been smoothed and from it two oval like voids have been carved out. Although they both have similar shapes, their distinct proportions, clearly set them apart producing two different forms with distinct dimensions – one narrower and one wider. When empty, the two voids establish a relation with a third void, the space under the slab of granite. At the same time their surfaces, which have been produced by the chisel used to carve them out, and the raw edges of the volume are related through the smooth and even horizontal surface, which connects them all.

©

©

When placed outside in the rain, the voids slowly fill up with rainwater. The narrow one, of less volume filling up faster; the wider one, more slowly until they are both full and the rain produces a continuous layer of water with two deeper pockets. When the rain has stopped and the water has dried from the black granite, two surfaces of water are left. Their surface tension is slopping them slightly up at the border. Two voids have become two surfaces; our subconscious connects them underneath. They clearly must be connected somehow, they are some sort of discontinuous body.

From certain points of view the water seems crystal clear and the space of the void, now full of water, becomes visible. Its inner surfaces are much darker now. Under different light conditions the horizontal surfaces act as some sort of mirror, reflecting their surroundings. Whereas the reflection on the granite is blurred, the two surfaces of water render a perfect image instead. Both of them are reflecting a segment of the same image, mirrors of the real, only disturbed by a leaf that might fall on them or some vibrations, which might move the water surface and blur what can be seen.

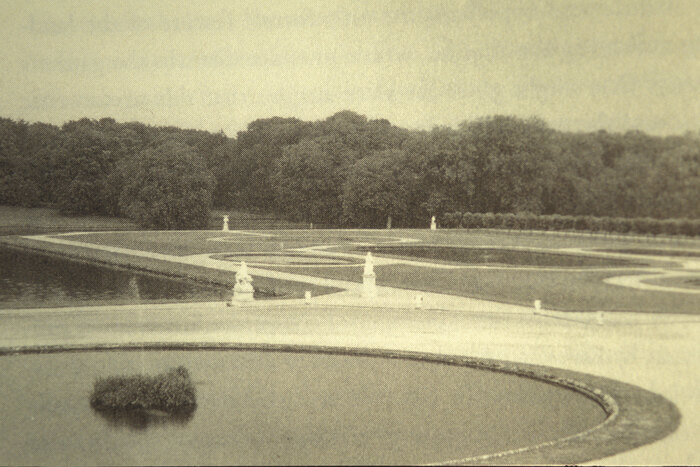

Circa 30 km north of Paris along the small river Nonette lays the Château de Chantilly. The oldest existing part of the Château is the Petit Château, which replaced an older structure and was designed as part of a 20.000 acre estate in 1560 by architect Jean Bullant for Anne de Montmorency, a member of François I’s court. At the end of the 17th century André Le Nôtre, the landscape architect of Versailles, designed a 270-acre portion of the estate in the north-east of the castle for the Prince of Condé Louis II de Bourbon. Le Nôtre created a completely different setting.

His layout for the park does not put any of the buildings of the Château in the central point of his composition. It is not the architectural building which dominates its surroundings but the other way round a composition where the large style flowerbeds and the immense mirrors of water together with all the different water features incorporate the Château. Of all his creations this was Le Nôtre’s favourite work.

The central axis of the park consists of a 330 per 80 metres big water surface and a one km long clearing extends it on the other end. To each side of the central water surface there are extensive flowerbeds with large mirrors of water inside and at its end the central water surface is crossed by a 2.5 km long Grand Canal, which was created by Le Nôtre by diverting and ponding the waters of the Nonnette. On the other side the Château is surrounded by additional water surfaces, which follow the geometry of the castle instead of the geometry of the park.

©

©

Le Nôtre supplements the rigour of the continuity of visual perspective by the continuous presence of water. The extensive parterres and water features of the park connect the Château to a different scale or more precisely still to different scales. Le Nôtre’s design changes the place profoundly. A castle with a small river at some distance becomes some sort of flatland, where a lace of a thin layer of precisely drawn flowerbeds and the castle appear to be floating on and in water. Here water apparently exists ad infinitum and the ground itself resembles just a thin carpet covering the water occasionally.

The large mirrors of water in the garden reflect the sky, everything around them and produce a simulacrum of what there is. But what is more important, through its doubling the real can be perceived as a reflection of its own simulacrum producing the possibility of a sort of vertigo. Here time exists as moments. Water resembles some sort of animated matter, its continuous movement, its mysterious depth, where the unknown resides, attract out attention. There is a direct connection between the subconscious of water and the subconscious of the beholder. Water as medium has a physical dimension as well as a psychological dimension. Water is a medium of contemplation presenting us with the incessant modulation of our surroundings or with complete silence. What exists in ourselves is temporarily suspended; around us wind moves the plants of the park and the surface of the water.

At Chantilly water is not only a mirror to be looked at, but also a distance to be measured. The surfaces are dimensioned in a way as to perceive certain features from a distance, sometimes completely loosing their scale. A precious exercise of architectural design: to draw a facade to be seen from the distance of a surface of water, or: to draw a volume to be completed by its own reflection. Both of them have been applied at Chantilly.

©

©

Water is able to create a distance, to separate, while it is producing shifts in scale and connecting discontinuous parts at the same time. Water always produces an apparent void, a space which cannot be experienced with your body easily, but which is crossed by your view continuously. This void is a space of desire, where you cannot go by normal means, but which, when crossed, produces a state of delight. When during strong winter seasons the White Lake in the alps suddenly freezes, the mirror of the ice still contains the relief of the moving water and the joy of walking on it is quite similar to the joy of swimming or of sailing on a boat, it is a spatial conquest.

©

©

Air as a gas and water as a liquid are considered both fluids, as opposed to the solids, which complete them. Gases and liquids share different phenomena. Water in particular can change between a gaseous, a liquid and a solid state. While solids keep their form, fluids have a more complex relation with form.

Although water could be described at first glance as formless, it possesses very strong form defining forces. As an element it is never defined a priori, but is continuously ready to be defined from outside, while at the same time defining its outside. As a matter of fact, water draws its very own geometries at different scales and dimensions continuously.

Naturally flowing water always tries to flow in a meander. Riverbeds are continuously shaped by the wounded water stream of primary and secondary vortexes. Warmer currents inside colder oceans draw large loops, which shift constantly. A huge variety of unicellular water fauna actually condensed the wounded stream of water currents as their body form and uses them as a means of transportation. Water, like other fluids, produces waves, which can be also found in the movement patterns of fishes such as rays. Fluids produce other forms too, such as whirls and vortexes, which again resurface in other material settings.

Naturally flowing water always tries to flow in a meander. Riverbeds are continuously shaped by the wounded water stream of primary and secondary vortexes. Warmer currents inside colder oceans draw large loops, which shift constantly. A huge variety of unicellular water fauna actually condensed the wounded stream of water currents as their body form and uses them as a means of transportation. Water, like other fluids, produces waves, which can be also found in the movement patterns of fishes such as rays. Fluids produce other forms too, such as whirls and vortexes, which again resurface in other material settings.

©

©

Water continuously reads what is around it, while at the same time inscribing itself in the material, which it reads. Mountain torrents carve their distinct geometry in granite or porphyritic volcanic glass, while at the same time they are shaped by the stone. At other scales water shapes whole territories producing a distinct topography out of inhomogeneous material settings. A series of watersheds develops and produces a system of streams and rivers naturally. Elsewhere rivers produce meander and deltas. Everything, which water encounters, is shaped by it: terrain, stones, rocks but also trunks and other elements.

©

©

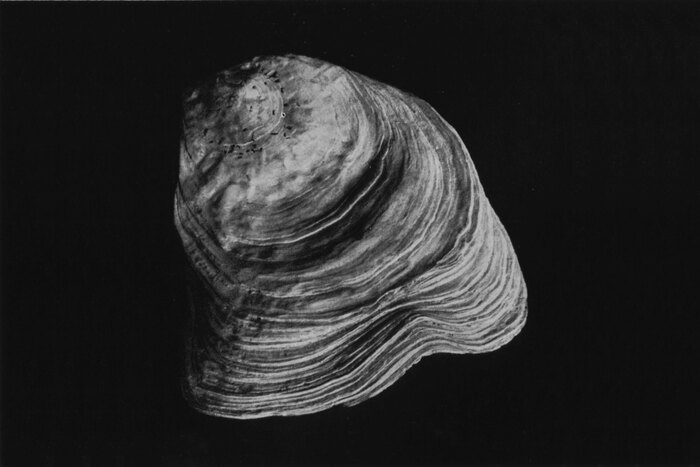

Sometimes we encounter the geometries of fluids in solids. This might happen, because the solid follows the same physical principle, has been shaped by a fluid or quite simply was a fluid itself and by changing its state consolidated the geometry of its former existence. We encounter fluid rocks, stream like trunks, vortex like shells and other forms.

©

©

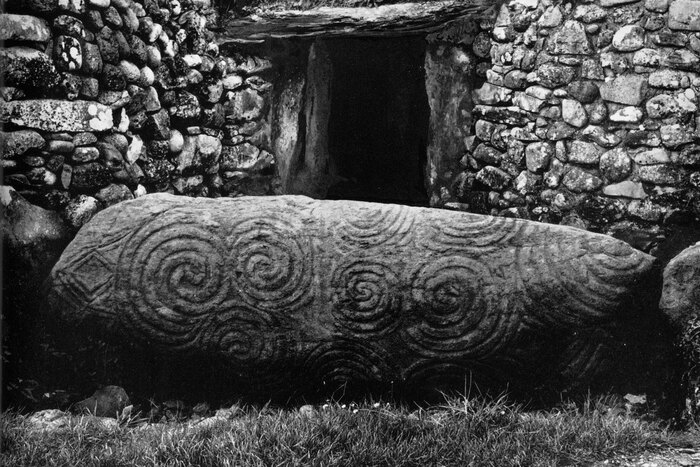

Water draws, but at the same time water is drawn and has to be drawn. Sometimes, because it has to be represented as a symbolic value, as a message. Waves and vortexes used to be drawn or incised in stone in order to represent water, in order to transform stone into water

Sometimes it is simply necessary to give a shape to water and a form has therefore to be drawn, a form for a certain area or a container for a certain amount of water. But at other occasions precise effects are desired and water is given a form in order to produce visual effects such as reflections, climatic effects such as a certain microclimate, temperature or humidity. Small ponds, canals and water mirrors can be used in order to bring phenomena from different contexts to an expressive plane, which might remain hidden otherwise.

©

©

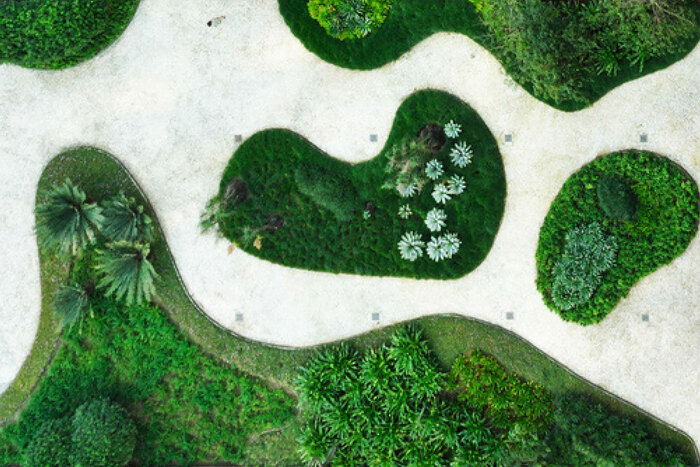

Sometimes in order to transfer the spatial character of fluids into other settings, their geometries are used. When Roberto Burle Marx draws his horizontal drawings, the fluid character of the reference is transferred into space, even when no fluid is present.

©

©

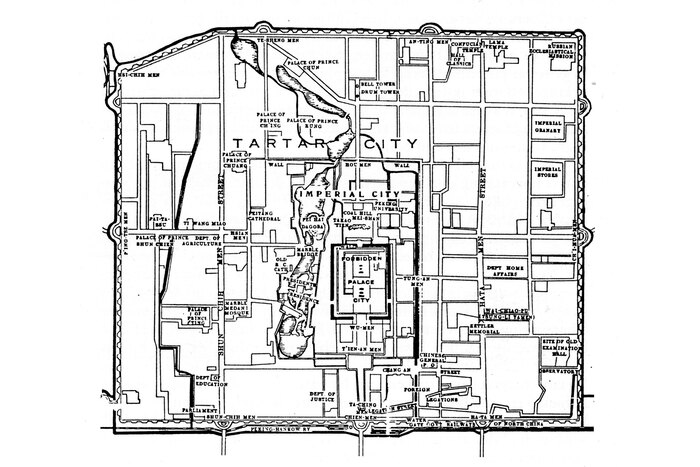

Beijing was laid out according to an architectural planning approach, which involved two figurative elements, that had to be combined in a way, which mutually generated and balanced each other in order to achieve a unified whole. Central Beijing followed a completely regular chessboard-like layout on the topography of a basin, which opens towards the south-southeast. The two figurative elements, which were used to design Beijing were topography and water. In a certain distance from the centre of Beijing the rivers Yung-ting-ho and Pei-yün-ho reach the periphery of the city. Much of the water found to the northeast of the city was brought to the city through a refined hydraulic system, traversing the city in southeast direction. The artificial rivers, lakes and islands, which were designed inside the city-limits, were drawn with their very own geometry, which were completely different from the regular geometry of the settlement. The Forbidden City was accompanied with three large, irregular lakes to the west. The excavated material, which resulted from the construction of the three lakes, was used to build an artificial mountain to the north in the geometrical centre of the old city. Excavation and elevation were interventions which balanced each other and the resulting artificial topography was complemented by the water which had been brought here and adjusted, where necessary, though additional modifications.

©

©

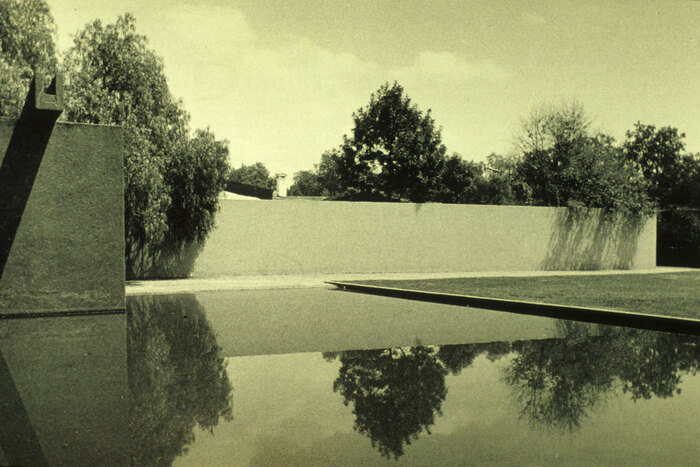

When Luis Barragán designed the Fuente de los Amantes in 1964, only very few elements were sufficient to built a true masterpiece of architecture: a pink wall limits the space to the north and to the west, two smaller walls carry the aqueduct; lush vegetation tops the rosé wall, a pool of water is fed by the cascade of water from the aqueduct. The pool and the pavement in front of the pool are covered with pave, while the rest of the terrain is covered with lawn. Two walls, the right colour, vigorous vegetation, the sky and water are everything you need.

Stephan Jung

KEYWORDS

AVAILABLE

SAFT 04 WATER

is also available as part of:

Buy it now !