CONTENT

Toni Frissell was one of the first female photographers working for major magazines. Born in 1907, as Antoinette Frissell to a New York upper class family she apprenticed with Cecil Beaton and Edward Streichen but it was her brother Varick Frissell, a documentary filmmaker fascinated by the genuine wilderness of north Canada, who taught her the basics of photography. His work includes the first large screen production made in and about Canada which relied on filming as well as sound recording on location instead of the technics of simulation as present in a studio. In The Viking he applied the knowledge and technics of a documentary filmmaker to the story telling of a Hollywood film. His interest in landscape and attentiveness for a place very much impacted the attitude of Toni Frissell as a photographer. She brought models outside of a studio and on location. Not being interested in technical effects but focusing on the unselfconscious spontaneity of her photos she relied on the materiality of the world as her readymade studio.

©

©

In 1937 she did a photographic project for Vogue on Mexican women. Although the article Señoritas de Mexico, written by Alice-Leone Moato, which is illustrated with these photos, mainly focuses on members of the upper society, it starts with a full-page colour photo of Frida Kahlo at a time when the magazine was still in huge parts in black and white. Of the photo shoot there exist some contact sheets, a series of middle format 6X6 images in black and white as well as the colour photo published in Vogue. On this photo Frida Kahlo wears traditional Mexican clothes: a long white cotton skirt ending on the ground with an amble flounce of the same material, a blue blouse with white dots, a high round neck and frills applied around her collar as well as to the sleeves. Blouse and skirt are complemented by a wide purple shawl, which she extends or wraps around her on the photos, a brooch on a necklace and two earrings. Her hair is braided to two plaits with a red strap at each end.

The pictures were taken in front of a large agave with Frida Kahlo standing or sitting in front or beside it. All the pictures were taken from a low point of view producing the effect of prolonging the figures of both Frida Kahlo and the agave. White, blue, petrol green, purple, red and the colour of Frida Kahlo’s skin, the geometry of the agave and Frida’s body complemented by the fluidity of the shawl placed against the sky.

These photos are neither pictures of Frida Kahlo nor of the Agave, not of Frida Kahlo in a Mexican landscape, but of the Mexican landscape in Frida Kahlo or with other words Frida Kahlo as part of the Mexican landscape and vice versa.

The pictures were taken in front of a large agave with Frida Kahlo standing or sitting in front or beside it. All the pictures were taken from a low point of view producing the effect of prolonging the figures of both Frida Kahlo and the agave. White, blue, petrol green, purple, red and the colour of Frida Kahlo’s skin, the geometry of the agave and Frida’s body complemented by the fluidity of the shawl placed against the sky.

These photos are neither pictures of Frida Kahlo nor of the Agave, not of Frida Kahlo in a Mexican landscape, but of the Mexican landscape in Frida Kahlo or with other words Frida Kahlo as part of the Mexican landscape and vice versa.

©

©

During the Second World War Toni Frissell went to the European front twice to take photos of the Red Cross as well as of women and African American in the armed forces. Here she took photos of the Tuskegee Airmen stationed in Ramitelli in South Italy in 1945. These photos are portraits of man in action, staged against their everyday surrounding of an airfield build in the middle of agricultural land not far away from the Adria. These are models in a different scenario. An airman suspended above the ground of the airstrip with harrowed ground in the background, the wing of the airplane is replicating the horizon, the airman sitting on it suspended in the air with the sky behind to emphasize his profile.

In another picture a pilot enters a shelter. Only a light source has been put inside the shelter to light up the interior and reduce the contrast between the bright sunlight entering from outside and the darkness of the interior.

In another picture a pilot enters a shelter. Only a light source has been put inside the shelter to light up the interior and reduce the contrast between the bright sunlight entering from outside and the darkness of the interior.

©

©

After the war was over Toni Frissell wanted to extend her subjects beyond fashion and started working for Sports Illustrated. During this time she did one of the first photos of the recently invented bikini. A girl lays on the smooth concrete surface of a quay, around her the curled surface of the sea with rocks visible underneath. The girl is taking a sunbath by covering her face with one arm as to protect her eyes from the bright sun, which covers her body and casts her shadow on the concrete underneath her. In another set she takes underwater photos of female bodies wearing white dresses suspended in weightlessness as if floating in space.

In all these cases she works en plein air documenting not an object, a dress or person, nor what can be encountered around them, but the relation between them. The object of her photo becomes a subject in a different encounter.

In all these cases she works en plein air documenting not an object, a dress or person, nor what can be encountered around them, but the relation between them. The object of her photo becomes a subject in a different encounter.

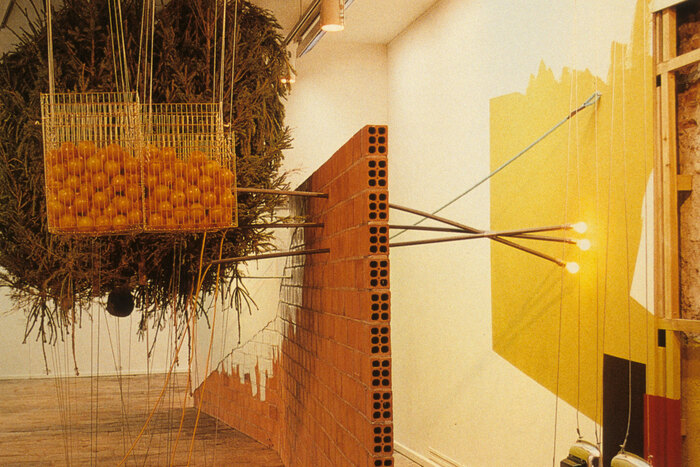

In her installation Sweet for three oranges from 1995 Jessica Stockholder places various objects inside the space of Galeria Montcada in Barcelona: 40 Christmas trees, 50 kg of oranges, four bird cages, a brick wall, air craft cable, two butane tanks and heaters, rope, roofing paper and roofing tar, paint, light bulbs and yellow electric cords, PVC piping and angle iron. The single elements have been extracted from the everyday life in a sort of collection of what there is. Most of them come directly from a supermarket or hardware store. They have been placed inside a space in relation to what has been there already: a room large 21 per 4.9 metres with a partition suspended from the ceiling of this white cube as its main architectural gesture. Inside the room a brick wall has been built dividing the space into two narrower ones. Seen from the entrance this wall appears to be part of the gallery since its opposite end is covered with white plaster and therefore melts with the white of the surrounding walls. In the centre the plaster had been left out and the white paint remained before even the paint vanishes and only the red of the bricks is what is left in front of the entrance.

©

©

On one side of this wall, angled irons are fixed to the ground and ceiling. Between them the Christmas trees as well as the oranges placed inside the bird cages are suspended in the air by thin wires. Three pieces of PVC piping stick through the brick wall, connecting both sides of it. Yellow electric cords have been plugged into power outlets on the opposing wall of the gallery, are running through the PVC piping and are connected to three yellow light bulbs attached to the other end of the piping.

Seen from the other side of the gallery the relation between the wall and the gallery changes. Half way through the gallery the wall folds slightly where it touches the overhanging partition. The other side of the wall has been painted in bright yellow and a patch of tar has been attached to the overhanging partition. On this second side the space between the brick wall and the wall of the gallery is narrower. While on the first side different volumes were suspended in the air, on this side there is the immateriality of drawing. Near the entrance a part of the white drywall has been cut out revealing the materiality of the wall underneath and a large yellow surface has been painted on the wall of the gallery covering part of the cut out. Other surfaces in different colours complement the composition and the three lightbulbs and two butane tanks with their heater are directed towards it.

In order for the installation to be site specific the architecture of the room had to be manipulated. The cut out and the different surfaces painted on the perimeter wall correspond to the trees and oranges suspended in space. Installation and architecture react to each other, but it is the purpose build wall, which mediates between both. This wall is part of both. It has been carefully positioned and attentively folded. Successively the objects, materials and colours were placed just like in painting. Through the wall various things are related to the place and to each other. Around it new systems emerge, build up and brake down, some of them material, some formal, some physical, some experiential, some functional, some by accident. The same strategies as in architecture apply: there is an in front and a behind, a left and a right, an above and a below. There is the materiality of things and the magic of drawing. Here formal relations build up between disparate elements, because they are positioned in a certain way around the spatial medium of a wall.

Seen from the other side of the gallery the relation between the wall and the gallery changes. Half way through the gallery the wall folds slightly where it touches the overhanging partition. The other side of the wall has been painted in bright yellow and a patch of tar has been attached to the overhanging partition. On this second side the space between the brick wall and the wall of the gallery is narrower. While on the first side different volumes were suspended in the air, on this side there is the immateriality of drawing. Near the entrance a part of the white drywall has been cut out revealing the materiality of the wall underneath and a large yellow surface has been painted on the wall of the gallery covering part of the cut out. Other surfaces in different colours complement the composition and the three lightbulbs and two butane tanks with their heater are directed towards it.

In order for the installation to be site specific the architecture of the room had to be manipulated. The cut out and the different surfaces painted on the perimeter wall correspond to the trees and oranges suspended in space. Installation and architecture react to each other, but it is the purpose build wall, which mediates between both. This wall is part of both. It has been carefully positioned and attentively folded. Successively the objects, materials and colours were placed just like in painting. Through the wall various things are related to the place and to each other. Around it new systems emerge, build up and brake down, some of them material, some formal, some physical, some experiential, some functional, some by accident. The same strategies as in architecture apply: there is an in front and a behind, a left and a right, an above and a below. There is the materiality of things and the magic of drawing. Here formal relations build up between disparate elements, because they are positioned in a certain way around the spatial medium of a wall.

©

©

Casa Malaparte has been placed on the peak of Cape Massullo underneath the cliff of Matermania at about 25 metres above sea level. This coastline is the most inaccessible part of the island of Capri. After descending a steep hang between pines and rocks along Via del Pizzolungo – there, where no beach is – suddenly a red volume appears. It has been placed on top of a rock, between green trees, in the sea.

After the last steps of the descent the path suddenly becomes a stair leading to a huge terrace of 45 metres by 9.5 metres with a white wall on it and the volume of a building underneath. This is the conquest of space, where there had been only a crest before. Here a smart manoeuvre has been carried out. The mass of a building was used to create the absence of it: a huge void dialoguing with the horizon, the wind, the sea and the sky. This is the realm of the continuity of smooth space in absence of scale.

A simple turn is enough to change the scenery completely. Now the terrace becomes a stair, becomes a path, becomes landscape. This is the spectacle of the material world: massive rocks covered with vegetation and the path getting lost in it. This is a view full of geometry; here infinite scales are compressed in one scene.

Casa Malaparte is the geometry of architecture mediating between the complex geometry of the rocks based on lines and the geometry of the sea-sky, based on trajectories and vectors. Here smooth space collides with striated space inside a rectangular terrace.

At the bottom of the scale a passage accompanies the building leading to a small plateaux right in front of it from where the building can be entered. From here a stair leads down to the sea where another plateau can be used to take a bath or board a boat.

Casa Malaparte is the geometry of architecture mediating between the complex geometry of the rocks based on lines and the geometry of the sea-sky, based on trajectories and vectors. Here smooth space collides with striated space inside a rectangular terrace.

At the bottom of the scale a passage accompanies the building leading to a small plateaux right in front of it from where the building can be entered. From here a stair leads down to the sea where another plateau can be used to take a bath or board a boat.

Inside the building there are three floors. The uppermost contains a large room with five windows, one in each corner and a smaller one behind the fireplace. Each of the large windows affords a different view. The first shows the cliff of Matermania with its pine trees, the second Cape Campanella, the third the Faraglioni and the fourth the stack of the Monacone. The fifth window has been inserted behind the fireplace making it possible to observe the nocturnal sea lit up by moon light while sitting next to a warm fire inside the room. At the same time the window, made of Jenaglass, transforms the house into a beacon visible from the outside, maybe from a boat arriving with guests for dinner.

In this place different architectural elements have been placed in relation to the world and each other, just like in the case of Toni Frissell and Jessica Stockholder. The terrace with its wall, the windows of the hall cut out of the massive walls, the different stairs outside, the windows in Malaparte’s office: everything relates to already existing features, but by relating to them, they produce them at the same time. Architecture is not about the application of a consolidated typology, but about invention. Carefully placed architectural elements establish a series of relations with the existing physical world around it producing an assemblage between an architectural device and the surrounding landscape. Casa Malaparte inscribes itself into the world around it. It is the author of the landscape – as Curzio Malaparte said – and vice versa the surrounding landscape inscribes itself into the building. One does not produce the other, but both are the product of the same miracle. They are a narrative invention, built by a writer aware of the literary tools capable of constructing experiences and evoking emotions, if possible of surreal dimensions. Casa Malaparte combines – like the inventions of the baroque – different psychological states: the plane of transcendence of the terrace with sudden moments of immanence.

Here just like in the case of the photos of Toni Frissell or the installations of Jessica Stockholder the importance resides not in the creation of an object but in the production of a space rich in relations.

Here just like in the case of the photos of Toni Frissell or the installations of Jessica Stockholder the importance resides not in the creation of an object but in the production of a space rich in relations.

Stephan Jung

KEYWORDS

AVAILABLE

SAFT 05 ENSEMBLE

is also available as part of:

Buy it now !